How do likes and reactions as interactional features on Facebook status updates posted in 2016 extend narrative evaluation? |

|||||||||||||

| While previous research has investigated Facebook likes, their role in evaluating online content, and expanding evaluative practices in an online environment, in 2016 reactions were newly-released on Facebook, and have not yet received much scholarly attention. Therefore, in this study I analysed the meanings attributed to likes and reactions by Facebook users and how they were actually employed to respond to Facebook status updates. I compared my results with previous studies to determine how far the use of likes and reactions have extended |

| ULAB17 Abstract | |

| File Size: | 149 kb |

| File Type: | |

When asked 'what is a story?' we might think of a novel, a news report, or an advertising campaign involving the interaction of relatable characters. Narratology research has expanded the narrative concept by recognising that a story does not necessarily have to follow a past-tense, linear, chronological structure (Labov, 1972). A narrative can be based in the present or portray future projections of events (Georgakopoulou, 2007), can be co-constructed by multiple contributors, or co-tellers, and embedded in, and refer, to different contexts (Ochs & Capps, 2001). Narratives can take the form of newsflash stories, they develop through the comments sections of shared posts, and also reflect offline shared knowledge in an online environment. Page, Harper, and Frobenius (2013) situate these reformed narrative characteristics into the networked narrative, which involves collective participation and co-construction of shared stories through the use of communicative online affordances, such as likes and reactions and comments, which can be used to co-construct, extend, and evaluate status updates on Facebook. However, it is maintained in the literature that narrative evaluation is an integral part of the narrative concept.

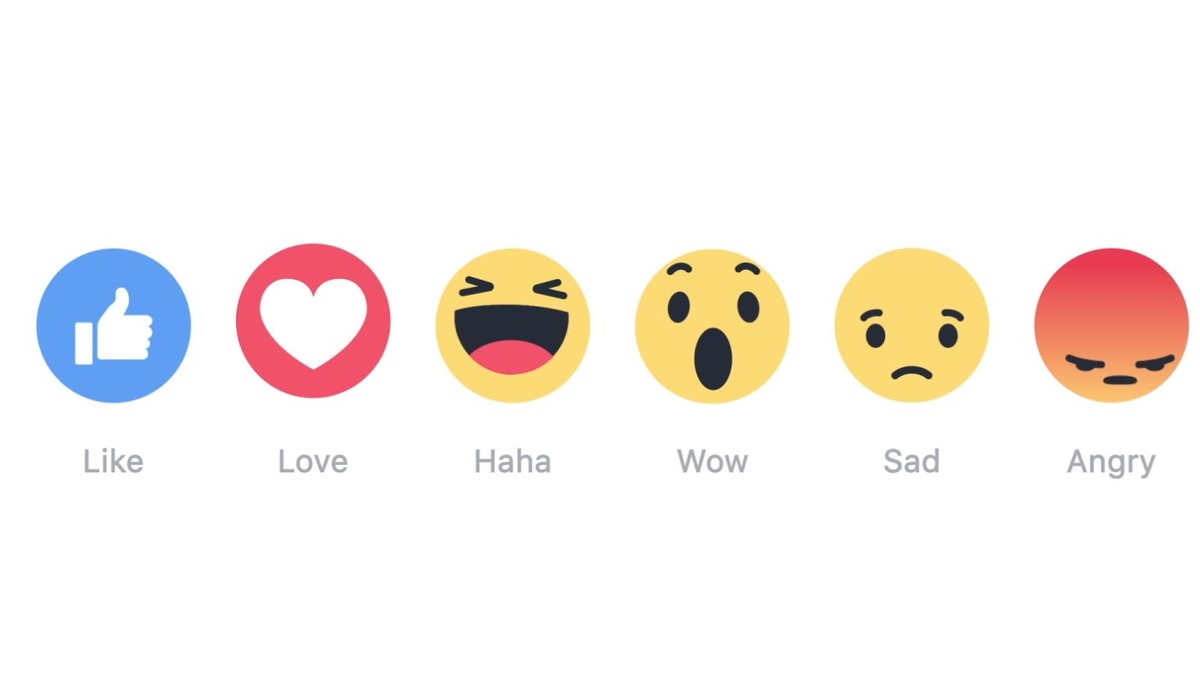

| 3. Evaluation in the Networked Narrative Likes and reactions are interactional features that function as responses to Facebook status updates (Herring & Dainas, 2017; figures 1 & 2). Likes, displayed as thumbs-up graphicons, were introduced to the Facebook infrastructure in 2009 as a "uniform positive response", which encouraged Facebook users to positively respond to and evaluate content such as status updates and shared posts (West, 2015: 8). Narrative researchers Page, Harper, and Frobenius (2013) and West (2015) have investigated the nature of the networked narrative, collating data from Facebook status updates composed in 2008, 2010, and 2012 in a longitudinal study, and 2013 in a comparative study. They found that likes functioned as an |

a) To state a preference for the content;

b) As a 'minimal response' that required only low engagement and commitment to the content, compared to commenting, which involves high engagement (Ochs & Capps, 2001);

c) As a form of positive facework that supported offline relationships (Brown & Levinson, 1987), or

d) To demonstrate solidarity.

Due to the use of multiple meanings for one graphicon, this resulted in the meaning of like evaluation to become ambiguous.

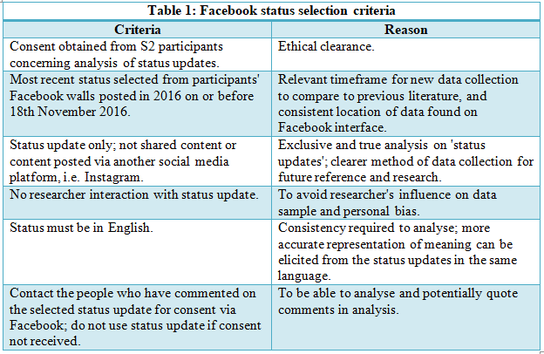

The study consists of three stages of data collection. Stage 1 (S1) was a SurveyMonkey survey distributed on the researcher's Facebook network and aimed to establish self-reported use and meanings of likes and reactions. 30 responses from participants aged 18-24 years were analysed. S1 participants volunteered to participate in Stage 2 (S2), which analysed 10 Facebook status updates posted between 31st July to 17th November 2016, selected following the criteria detailed in table 1.

Note: The majority of S3 data is discussed in the SymPol10 post, which discusses likes and reactions operating as politeness and facework strategies and their impact on user's self-esteem. To read the SymPol10 post, click here.

5.1. Making Comparisons Between Reported and Actual Usage

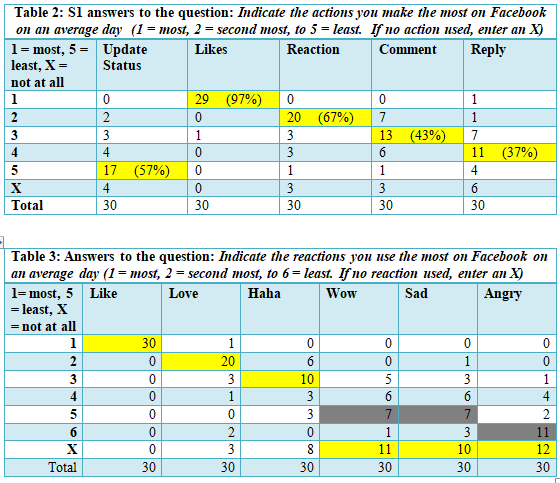

All 30 participants aged 18-24 years self-reported using like, while 57% used reactions, on Facebook on an average day (table 2). Likes were the most frequent action (97%), followed by reactions as the second most frequent (67%). These results indicate an extension to and continued increase in evaluative practices on Facebook in 2016, supporting previous findings that indicate this trend (Hampton et al., 2011; Page, Harper, & Frobenius, 2013; Smith, 2014; Stinson, 2016). However, 100% of participants still reported using like the most out of the reaction continuum, followed by love (50%), and haha (25%), suggesting that likes are still the most prevalent evaluative interactional feature on Facebook (table 3).

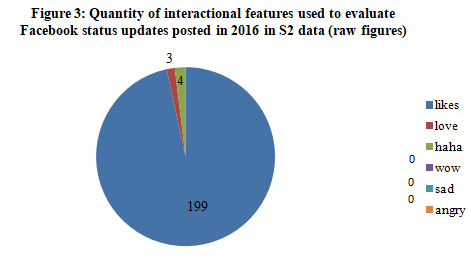

Interestingly, S1 and S2 results show a negative relationship between negatively attributed reactions and the frequency of use. The negative relationship means that the negatively attributed reactions (such as wow, sad, and angry) are used less frequently than positively attributed reactions (e.g. like, love, and haha). This may reflect members' preference for more positive evaluations. For instance, the angry reaction potentially satisfies members' desire for a dislike button (Kokalitcheva, 2016). Disagreement and dislike were reportedly attributed to angry by 5 and 3 participants respectively. However, its absence in the S2 and limited prevalence in S1's reported meanings implies that angry is not frequently used, and the comparative frequency of positive reactions, suggest that the preferred employment of interactional features are those that indicate a positive signal.

S1 and S3 data revealed that a large variation of meanings and functions are attributed to likes and reactions by Facebook users. It implies that the more these interactional features are used as evaluative practices, the more their role of evaluation expands in this online environment. Of the top three most attributed meanings to likes and reactions, likes, sad, and haha appear to be the most agreed upon. However, likes had the most variety of meanings across the whole participants sample.

Commonly reported meanings attributed to like were to signal agreement, positive preferential sentiment, and acknowledgement of the status content. These meanings reflect West's (2015: 55) research that found like function similarly to "ok", conveys a sense of "attention, acceptance, support, recognition, and appreciation". 'Agreement' functions similarly to a positive feedback cue, such as a back-channel (e.g. 'ok' or 'yeah') or a non-verbal positive response that resembles a gesture similar to a nod of the head in offline conversation (Goffman, 1981: 12).

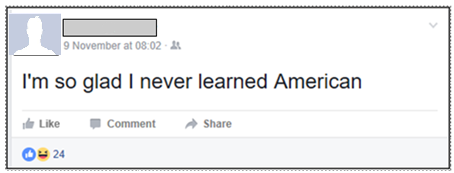

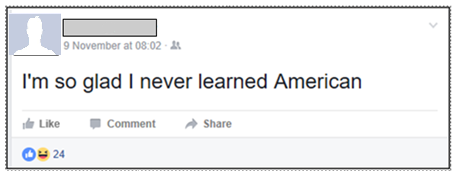

| For example, one of the status updates analysed was posted by a Modern Languages student on 9th November 2016, the day after the US Presidential Election, with the statement: "I'm so glad I never learned American". The status' narrative context is embedded in the offline world. The status' timestamp draws a pragmatic link between the US Presidential Election, the |

Interestingly, the author intended the status to be humorous (stated in S3). 87% participants (26) stated that they use haha to mean that they find the status content funny. The presence of the haha reaction evaluating the status demonstrates the function of haha to display amusement; however, only 1 participant of 24 chose to evaluate the status in this way. Although author and audience humour will differ, having only one haha present (the rest being likes) highlights an overlap between the use of likes and reactions; haha, in this case. For example, one Facebook user stated that the status "made me laugh so hard", and yet merely liked the status despite evidently finding it funny. Likes' high-frequency usage could also allude to the practical, functional affordances of like interactions compared to reactions (Gibson, 1977; Hutchby, 2001: 444). West and Trester (2013: 145) suggest that like acts as a "minimal effort response" to statuses on Facebook. The ease with which it is to select like as opposed to a reaction may influence the quantity of likes used by Facebook members compared to reactions. One can click on the PC or tap on a smartphone for likes, which is easier and quicker than a click-and-hold on PC or press-and-hold on smartphone for reactions. Likes are much more efficient a response than reacting or even commenting and the comparative popularity of likes might be due to, at least in part, to satisfy Facebook users' desire for fast-paced and content-saturated online environment, where efficiency is prized over effort.

The idea that likes (and by extension, reactions) can be used to display solidarity has been discussed by Page, Harper and Frobenius (2013: 199). The mass of likes compared to one haha in the example status update could demonstrate that the majority of people prefer to respond similarly to others; however, those who wish to stand out respond with reactions, or differently, to the cohort. This idea could provide another explanation as to why likes are used considerably more than haha and reactions in general, despite perhaps some statuses warranting particular reactions as an evaluative response (e.g. being humorous).

Herring and Dianas (2017, in press) found that emotional response graphicons (emoticons), are the most commonly and frequently used. However, human emotion is too complex to be represented as a single graphicon, so perhaps it is no surprise that "people often disagree on the sentiment and meaning of the same visual representation" (Miller et al., 2016, quoted from: Herring & Dianas, 2017, in press: 2), resulting in multiple, different uses and ambiguous meanings.

Likes and reactions as interactional features have afforded an increase in and an extension to evaluative practices when responding to status updates on Facebook. The use of likes and reactions create a co-evaluation from multiple users that embed the status in both online and offline contexts and indicate members' preference for positive evaluations on Facebook. Despite reactions being intended to clarify evaluations (Newton, 2016), likes are still used considerably more than reactions in 2016. It is argued that this could be due to numerous factors: a) likes' familiarity and integration in Facebook-user habits and competency compared to reactions (Eisenlauer, 2014); b) multiple meanings already attributed to likes before reactions were released; and c) the ease of practical and functional affordances of using likes as a "minimal effort response" over reactions (Gibson, 1977; Hutchby, 2001: 444; West & Trester, 2013: 145). Additional longitudinal research for likes and reactions would determine clearer conclusions and clarify the propositions made in this study. In addition, it would serve to track the quantity and frequency of like and reaction usage over time. Perhaps extending the investigation likes and reactions over multiple online networking platforms such as blogs, news articles, other social media websites, would determine whether similar meanings and functions are attributed to likes and reactions in various online environments.

Cite: Ford, S (2016) How do likes and reactions as interactional features on Facebook status updates posted in 2016 extend narrative evaluation? [Online] Available from: https://samantha-ford.weebly.com/projects--news/undergraduate-linguistics-association-of-britain-2017-ulab17.

- Brown, P. & Levinson, S. (1987) Politeness: Some universals in language usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Eisenlauer, V. (2014) Facebook as a third author - (Semi-)automated participation framework in Social Network Sites. Journal of Pragmatics. Vol. 72: pp. 73-85.

- Georgakopoulou, A. (2007) Small Stories, Interactions and Identities. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Gibson, J. (1977) The theory of affordances. In: Shaw, R. & Bransford, J. (eds.) Perceiving, Acting and Knowing: Toward an Ecological Psychology. pp. 67-82.

- Goffman, E. (1981) Replies and responses. In: Goffman, E. Forms of Talk. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Hampton, K.; Goulet, L.; Rainie, L.; & Purcell, K. (2011) Social networking sites and our lives. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech [Online] Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/2011/06/16/social-networking-sites-and-our-lives/. [Accessed: 8th November 2016].

- Herring, S. & Dianas, A. (2017, in press) "Nice Picture Comment!": Graphicons in Facebook Comment Threads. Proceedings of the Fiftieth Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. [Online] Available from: http://ella.slis.indiana.edu/~herring/hicss.graphicons.pdf [Accessed: 1st December 2016], OR http://hdl.handle.net/10125/41419 [Accessed 11th December 2017].

- Hutchby, I. (2001) Technolgoies, texts and affordances. Sociology. Vol. 3 (20), pp. 441-456.

- Kokalitcheva, K. (2016) Facebook's Iconic 'Like' Button Gets More Emotional. FORTUNE. [Online] Available from: http://fortune.com/2016/02/24/facebook-like-reactions/. [Accessed: 2nd November 2016].

- Labov, W. (1972) Language in the inner city. Philadelphia PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Miller, H.; Thebault-Spieker, J.; Chang, S.; Johnson, L.; Terveen, L.; & Hecht, B. (2016) Blissfully Happy or Ready to Fight: Varying Interpretations of Emoji. [Online] Available from: http://wwwusers.cs.umn.edu/~bhecht/publications/ICWSM2016_emoji.pdf. [Accessed: 16th December 2016].

- Newton, C. (2016) Facebook rolls out expanded like button reactions around the world. The Verge. [Online] http://www.theverge.com/2016/2/24/11094374/facebook-reactions-like-button.[Accessed: 2nd November 2016].

- Ochs, E. & Capps, L. (2001) Living Narrative: creating lives in everyday storytelling. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Page, R.; Harper, R.; Forbenius, M. (2013) From small stories to networked narrative: The evolution of personal narratives in Facebook status updates. Narrative Inquiry. Vol. 23 (1): pp. 192-213.

- Smith, C. (2016) Facebook Statistics and Facts. DMR Stats|Gadgets. [Online] http://expandedramblings.com/index.php/by-the-numbers-17-amazing-facebook-stats/. [Accessed: 8th November 2016.

- Stinson, L. (2016) Facebook Reactions, the Totally Redesigned Like Button, is Here. Wired. [Online] https://www.wired.com/2016/02/facebook-reactions-totally-redesigned-like-button/. [Accessed: 2nd November 2016].

- West, L. (2015) Responding (or not) on Facebook: A Sociolinguistic Study of Liking, Commenting, and other Reactions to Posts. A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements of the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics. Washington: Georgetown University.

- West, L. & Trester, A. (2013) Facework on Facebook: Conversations on Social Media. In: Tannen, D. & Trester, A. (eds.) Discourse 2.0: Language and New Media. Washington: Georgetown University Press.

Leave a Reply.

Categories

All

Academic Advice

Academic Research

Awards

Collaborations

Conferences

Courses

EMMA Project

Fundraising

Partnership With Big Cat Agency

Press

Projects

Publications

Research Experience

Teaching

Testimonials

Training

Workshops

Archives

October 2022

June 2022

May 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

December 2020

October 2020

July 2020

June 2020

March 2020

February 2020

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

April 2019

November 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

October 2017

September 2017

July 2017

April 2017

July 2016