|

How do likes and reactions operate as interpersonal politeness strategies when evaluating Facebook status updates posted in 2016?

Facebook status updates, identifying when they operate as politeness strategies. Three stages of data have been collected: a self-report survey, a sub-sample of status updates, and a contextual questionnaire for status update authors. Likes and reactions were found to operate as interactional, interpersonal, and facework strategies on Facebook. Likes and reactions are employed more for positive (than negative) evaluation, as a means to signal endorsement, and as a supportive minimal response that emulates offline positive feedback cues. Likes are particularly used as a form of facework; to signal to the status author that their status has been 'heard', read, and acknowledged (West, 2015: 54). Meanwhile, reactions such as love and haha can be used to maintain or display offline relationships. The small selection of status updates analysed in this study provides an indication as to how likes and reactions are used as positive, supportive, politeness strategies when evaluating Facebook status updates in 2016.

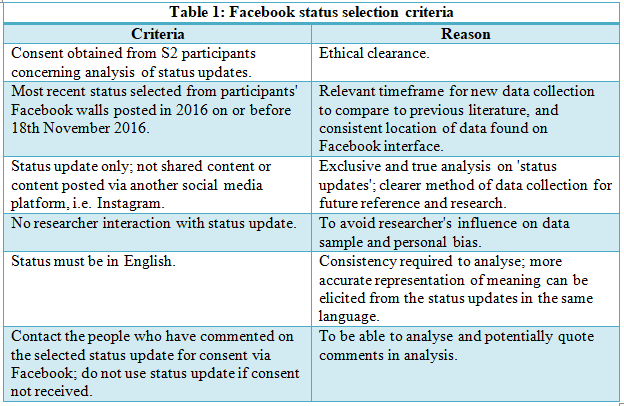

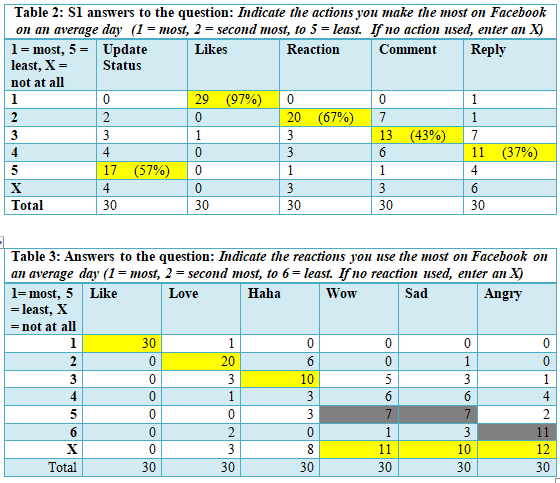

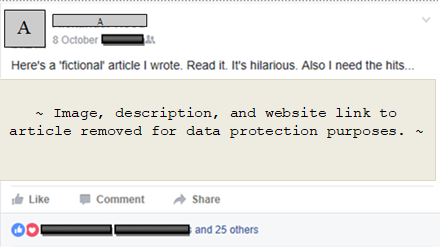

2. Likes as an Evaluative Practice Released in 2009, likes were introduced to the Facebook infrastructure as a "uniform positive response" to Facebook status updates and shared content (West, 2015: 8). The use of like as an evaluative tool on Facebook has been increasing since 2009 (Page, Harper, & Frobenius, 2013). While this may have been due to an increased number of members on the social networking site during this period (Hampton et al., 2011), Page, Harper and Frobenius (2013) found that the use of like doubled over two years (2010-2012) across a fixed sample of 60 Facebook members. This indicates an augmenting trend of using likes as a means for evaluation. Evaluation is an integral part to interaction, and its prevalent use on Facebook suggests that like has become a part of interpersonal and interactive practices in this online environment. However, narrative researchers Page, Harper, and Frobenius (2013) and West (2015) have found that despite the apparent simplicity of the like graphicon (thumbs-up), likes are being used to convey multiple meanings, extending the evaluations attainable for Facebook members when using them to respond to status updates. Some of the most frequent evaluations include: a) Stating a preference for the content; b) Acting as a 'minimal response' that required only low engagement and commitment to the content, compared to commenting, which involves high engagement (Ochs & Capps, 2001); c) Functioning as a form of positive facework that supports offline relationships (Brown & Levinson, 1987), and d) Demonstrating solidarity. However, due to the use of multiple meanings for one graphicon, the meaning of the like evaluation was found to be rather ambiguous and not as straightforward as originally imagined. Facebook is the largest social networking site on the internet and, as of September 2016, has around 1.18 billion daily active users, of which 1.09 billion access the site via mobile, and 24 million are in the UK alone (Facebook Newsroom, 2016; Smith, 2016). Graphicons, such as likes and reactions (figure 1), are used more on Facebook than on any other multimodal communication platform (Herring & Dainas, 2017). Reactions were released on Facebook in February 2016 with the aim to clarify the "inherent ambiguity" of likes and cover eventualities when like "doesn't feel appropriate" (Alison in: Newton, 2016) because "not every post is likeable" (Stinson, 2016). Having likes and reactions available on Facebook increases the opportunity for Facebook users to evaluate and interact with status updates and their social network. Due to the fact that reactions resemble emotions through their representation as emoticons, likes and reactions can operate using familiar emotional evaluations. However, considering the variation of meanings attributed to likes, has the introduction of reactions clarified evaluative and politeness (facework) practices on Facebook or increased the scope of attributed meanings in this online environment? This study investigates the meanings attributed to likes and reactions in 2016, particularly focusing on their function as politeness strategies. 3. Methodology To investigate how likes and reactions can operate as politeness strategies on Facebook, three stages of data were collected. Stage 1 (S1) was a SurveyMonkey survey distributed on the researcher's Facebook network, and aimed to establish self-reported use and meanings of likes and reactions. 30 responses from participants aged 18-24 years were analysed. S1 participants volunteered to participate in Stage 2 (S2), which analysed 10 Facebook status updates posted between 31st July to 17th November 2016, selected following the criteria detailed in table 1. Stage 3 (S3) asked all S2 participants to complete a questionnaire that collected contextual and extra-situational information on their status, such as their intention for posting the status and their reaction to the responses received. Although the exact meanings are not elicited from the liker themselves, the author's understanding of these interactional features gains an insight into their true functions. Note: For the purposes of the report of this study, the meanings that operate as politeness strategies will be described and discussed below. If readers are interested in additional meanings and uses of likes and reactions, then please read the sister report, How do likes and reactions as interactional features on Facebook status updates posted in 2016 extend narrative evaluation? 4. Results and Discussion: 4.1. Reported and Actual Usage of Likes and Reactions: A Preference for Positive Evaluation When asked to report what action participants use most on Facebook on an average day, 97% (N=29) reported liking, while 67% (N=20) reported using reactions, followed by 57% (N=17) updating their status (table 2). Like was the most frequent reaction type that participants used to respond to status updates on Facebook; whereas love was the second most frequent (67%, N=20), and haha as the third (30%, N=10) (table 3). These results suggest that likes are still the most prevalent evaluative interactional feature on Facebook. They also imply that Facebook users have a preference for positive evaluations over negative ones; like, love, and haha are clearly the top three most frequently used reactions, compared to wow, sad, and angry that are either infrequently used or are not used at all by members on Facebook on an average day. Indeed, the actual usage of likes and reactions evaluating Facebook status updates reflect the self-reports with regards to a preference for positive evaluations. Of the 206 likes and reactions that were responding to the sample of 10 status updates, these interactional features were all either likes (109), love (3), or haha (4). Similarly, the absence of wow, sad, and angry indicate that positively-attributed reactions are preferred, functioning as a positive signal, as initially intended by Facebook (Newson, 2016). Furthermore, the prevalence of positive evaluations contributes to Facebook being a more supportive and cooperative environment. The usage trends suggest, perhaps, that people want to be appreciated online and so by responding to status updates in a positive, rather than negative or critical, manner Facebook members portray themselves as polite, friendly, and supportive. Portraying oneself as having these qualities through the use of interactional features likes and reactions constructs a positive online image or aesthetic of the Facebook member, which thus encourages reciprocated feelings of appreciation and politeness between members online (Sugiyama, 2015). 4.2. Listening Like: An Acknowledgement of Attentiveness, Agreement, and Appreciation Likes have been attributed multiple meanings in the literature and in the 2016 data (see ULAB17), which indicates their multifunctionality online (Vandergriff, 2014). The increasing attributable variation of meanings and functions implies that the more these interactional features are used as evaluative practices, the more their role of evaluation expands in this online environment. Like is represented by a 'thumbs up' emblem, signalling a positive endorsement (Abner, Cooperrider, & Goldin-Meadow, 2015). Commonly reported meanings attributed to like in the S1 survey were to signal: agreement, a positive preferential sentiment, and acknowledgement of the status content. This reflects West's (2015: 55) research, which suggests that likes function similarly to "ok" and convey a sense of "attention, acceptance, support, recognition, and appreciation". These are maintaining the established preference for positive evaluations and are relatable to feedback cues given in spoken language, to encourage or endorse the speaker and indicate attentiveness of the listener (or reader). All 10 status updates analysed received likes. In this context, likes function as a signal to the author of the update that their status has been 'heard' (i.e. read) and are being acknowledged by others. West (2015: 54-55) coin this as the listening like, which acts similarly to a positive feedback cue or backchannel, such as 'yeah', 'ok', or 'right' in offline, spoken conversation (Yngve, 1970). Alternatively, these listening likes could be interpreted as emulating the non-verbal gestures; for example, as a nod of the head or smile (Page, Harper, & Frobenius, 2013). Liking a status can also function as a 'non-response' (West, 2015: iii) and "embed the very choice of having chosen not to comment" (West & Trester, 2013: 145), instead notifying the author that interlocutors (contributers) have read the status without committing to high involvement commenting (Ochs & Capps, 2001: 27). In this fast-paced and content-saturated online environment, efficiency appears to be prized over effort, due to likes being used considerably more than other interactions, such as commenting and replying to statuses (supported by S1 & S2 data). Interestingly, while the lack of comments on participants' statuses was not an issue, 90% (N=27) of participants stated that a lack of likes would have a negative effect on them. 60% (N=18) claimed they would feel "upset", "embarrassed", or "awkward" if they did not receive any likes; 50% (N=9) of whom said they would even consider deleting their status as a result of receiving no like responses. Taking into account the impact a lack of likes could have on Facebook users, likes can be interpreted as functioning as a type of positive facework that saves a poster's face (Brown & Levinson, 1987) by acting to avoid an unacknowledged status (Eisenlauer, 2014). Facework is a communicative, politeness strategy that aims to preserve dignity and reputation, by avoiding humiliation and embarrassment (Brown & Levinson, 1987). Likes therefore appear to have a realistic impact on self-esteem in addition to functioning as an evaluation of online narratives - status updates. 4.3. 'Sending love': Reactions Can Display, Maintain, and Develop Offline Relationships Even if Facebook users merely like a status update, rather than leave a message and comment, users are still indicating their involvement in the author's post, which could imply familiarity between authors and their network (Ochs & Capps, 2001). There were a selection of status updates that demonstrated likes and reactions being used to maintain and develop offline relationships. For example, familiarity and facework is also evident in use of love reactions and was used three times in the S2 data; however, in response to only one status (figure 2). The author posted a status update about a "fictional" article he wrote, with the intention of having his Facebook friends on his network read and respond to it. While the majority of responses to this post were through likes, suggesting that most users enjoyed the content of the article or appreciated the author's productivity in writing it. Interestingly, however, the status received three love reactions, from which all three Facebook users were the author's closest offline friends (informed by S3). While these Facebook members could have reacted to express love of the article's topic, their offline ties to the author as "close friends" (Meyerhoff, 2011: 198; S3) suggests that their reactions depend less on the content of the post and function more as positive facework to maintain their relationship with the author (Eisenlauer, 2014), known as 'offline anchorage' (Gross & Acquisti, 2005). In S1 data, 6 participants reported that they use love only with close friends, and 2 stated that the love reaction represented 'sending love' to the status author. The status above received a further 24 likes from other Facebook friends; however, their more distant relationship with the author (S3) perhaps influences their response to produce a like rather than love evaluation of the status. This behaviour could be equated to expressing love to a close friend in an offline context, as opposed to a more conservative 'fondness' or 'appreciation' of their friendship when not as closely tied offline (Eckert, 2000). 5. Conclusion The study has shown that Facebook users like and react when evaluating status updates as a form of interpersonal interaction in this online, social networking environment. The clear preference for positive evaluations over negative ones suggests that users are constructing positive, supportive, and cooperative online identities to be appreciated online (Sugiyama, 2015). In particular, the stronger emotional use of likes and reactions, such as love, can display and attempt to maintain both online and offline relationships among users' social network on Facebook and in real life. Facebook users also employ likes and reactions to operate as facework and politeness strategies, signalling endorsement and acknowledgement of previously unacknowledged status updates, which emulates offline conversation and the use of backchannels and positive feedback cues. Interestingly, the use of likes and reactions can have a realistic impact on self-esteem and so their use as facework appears to be an integral part of interpersonal interaction on Facebook. A further longitudinal study involving a larger status sample would increase the representative value of the current study's propositions, and would trace the uses and attitudes concerning likes and reactions as evaluative practices and politeness strategies on Facebook over time. Cite: Ford, S (2017) How do likes and reactions operate as interpersonal politeness strategies when evaluating Facebook status updates posted in 2016? [Online] Available from: https://samantha-ford.weebly.com/projects--news/the-10th-international-symposium-of-politeness-sympol10. References - Abner, N.; Cooperrider, K.; & Goldin-Meadow, D. (2015) Gesture for Linguists: A Handy Primer. Language and Linguistics Compass. Vol. 9 (11), pp. 437-449. - Brown, P. & Levinson, S. (1987) Politeness: Some universals in language usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. - Eckert, P. (2000) Linguistic variation as social practice: The linguistic construction of identity in Belton High. Malden: Blackwell. - Eisenlauer, V. (2014) Facebook as a third author - (Semi-)automated participation framework in Social Network Sites. Journal of Pragmatics. Vol. 72, pp. 73-85. - Facebook Newsroom (2016) [Online] http://newsroom.fb.com/company-info/. [Accessed: 11th November 2016]. - Gross, R. & Acquisti, A. (2005) Information revelation and privacy in online social networks. In: Proceedings of WPES'05, Association of Computing Machinery, Alexandra, VA. pp. 71-80. - Hampton, K.; Goulet, L.; Rainie, L.; & Purcell, K. (2011) Social networking sites and our lives. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech [Online] Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/2011/06/16/social-networking-sites-and-our-lives/. [Accessed: 8th November 2016]. - Herring, S. & Dainas, A. (2017, in press) "Nice Picture Comment!": Graphicons in Facebook Comment Threads. Proceedings of the Fiftieth Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. [Online] Available from: http://ella.slis.indiana.edu/~herring/hicss.graphicons.pdf. [Accessed: 1st December 2016], OR http://hdl.handle.net/10125/41419 [Accessed 11th December 2017]. - Meyerhoff, M. (2011) Introducing Sociolinguistics. [Online] 2nd Ed. Florence: Taylor and Francis. Available from - http://reader.eblib.com/(S(fu1semwri1o42ixevo5bzpan))/Reader.aspx?p=668428&o=1058&u=X74Qz lPFJUe2P3mveAc6Z95z2Ok%3d&t=1458300649&h=890860D3317B48F89EA6831F624AB8C4F77 199BB&s=43213365&ut=3459&pg=1&r=img&c=-1&pat=n&cms=-1&sd=2#. [Accessed: 8th Feburary 2016]. - Newton, C. (2016) Facebook rolls out expanded like button reactions around the world. The Verge. [Online] http://www.theverge.com/2016/2/24/11094374/facebook-reactions-like-button.[Accessed: 2nd November 2016]. - Ochs, E. & Capps, L. (2001) Living Narrative: creating lives in everyday storytelling. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. - Page, R.; Harper, R.; & Frobenius, M. (2013) From small stories to networked narrative: The evolution of personal narratives in Facebook status updates. Narrative Inquiry. Vol. 23 (1), pp. 192-213. - Smith, C. (2016) Facebook Statistics and Facts. DMR Stats|Gadgets. [Online] http://expandedramblings.com/index.php/by-the-numbers-17-amazing-facebook-stats/. [Accessed: 8th November 2016. - Stinson, L. (2016) Facebook Reactions, the Totally Redesigned Like Button, is Here. Wired. [Online] https://www.wired.com/2016/02/facebook-reactions-totally-redesigned-like-button/. [Accessed: 2nd November 2016]. - Sugiuama, S. (2015) Kawaii meiru and Maroyaka neko: Mobile emoji for relationship maintenance and aesthetic expressions among Japanese teens. [Online] First Monday. 20 (10). Available from: http://journals.uic.edu/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/5826/4997#author. [Accessed: 6th June 2017]. - Tian, Y.; Galery, T.; Dulcinati, G.; Molimpakis, E.; & Sun, C. (2017) Facebook Sentiment: Reactions and Emojis. Proceedings of the Fifth International Workshop on Natural Language Processing for Social Media. Valencia, Spain, 3rd-4th April 2017. Stroudsberg, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics. - Vandergriff, I. (2014) A Pragmatic Investigation of Emoticon Use in Nonnative/Native Speaker Text Chat. Language @Internet. [Online] Vol. 11(4). Available from: http://www.languageatinternet.org/articles/2014/vandergriff. [Accessed: 16th December 2016]. - West, L. (2015) Responding (or not) on Facebook: A Sociolinguistic Study of Liking, Commenting, and other Reactions to Posts. A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements of the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics. Washington: Georgetown University. - West, L. & Trester, A. (2013) Facework on Facebook: Conversations on Social Media. In: Tannen, D. & Trester, A. (eds.) Discourse 2.0: Language and New Media. Washington: Georgetown University Press. - Yngve, V. (1970) On getting a word in edgewise. In: Campbell, M. (ed.) Papers from the Sixth. Regional Meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society. Chicago: University of Chicago. Copyright © Samantha Ford 2017-2018

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

October 2022

|

||||||||

Photos from wuestenigel (CC BY 2.0), wuestenigel